The image is iconic, and the sound is unforgettable: the director, hand-cranking the old motion-picture camera, urging his young starlet to “… scream, Ann … scream for your life!”

That scream, and the actress who produced it, would become part of Horror Film history.

The movie, of course, was 1933’s KING KONG, and the actress was a 26-year old Canadian beauty named Fay Wray.

Born Vina Fay Wray in Cardston, Alberta, Canada, Wray came to Hollywood as a teen-ager, getting bit parts and supporting roles in a variety of pictures. Her major break came in 1928, in Erich Von Stroheim’s THE WEDDING MARCH. Her first genre role came in 1932, and her last in 1935, but in those three short years she became the first true Horror queen. The amazing part of her story is that she owes that status almost entirely to five films released in 1932 and ‘33: DOCTOR X; THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME; THE VAMPIRE BAT; THE MYSTERY OF THE WAX MUSEUM; and, naturally, KING KONG.

Volumes have been written about KING KONG, analyzing every characteristic of the film, from the technical aspects of Willis O’Brien’s stop-motion animation to the psychosexual subtext of the plot.

Tens, perhaps hundreds, of thousands of words have been devoted to Wray’s performance in that film, and I’ll pass on adding to that total in this article.

I want to examine those four films that preceded KONG, the four little known gems in the crown of Horror’s first Queen.

DOCTOR X—(1932)

Starring Lionel Atwill, Preston Foster, and Wray, and directed by Michael Curtiz, Warner’s DOCTOR X is a very good little film about a cannibalistic “Moon-Killer,” who strikes under the full moon.

Filmed in Two-Strip Technicolor, an early color film process, the restored film has an odd, greenish cast to it that is strangely effective for the subject.

Curtiz, who would later direct what some feel to be the greatest film ever, 1943’s CASABLANCA, kept this film moving at a good pace overall, though there are points where the comedy relief wears thin.

Wray portrays Joan Xavier, the daughter of the titular Dr. Xavier, who is played wonderfully by Lionel Atwill.

As lovely as ever, she plays the role a bit too broadly, and for some reason seems as jittery as the proverbial long-tailed cat.

Still, it’s always easy to enjoy Wray on-screen, and this film is no different.

The true star of this movie, however, is Lionel Atwill, and he shows that he can chew scenery with the best of them. The best scene in the film involves Joan reenacting one of the murders, playing the role of the young victim. Her father and those suspected of being the “moon-killer” are strapped into chairs, watching what they believe to be a reenactment of the latest killing, as devices record their reactions. However, the real killer has taken the place of the reenactor, and to their horror they realize Joan is being murdered in front of them, as they sit helpless. Curtiz does a masterful job building the suspense as the scene unfolds, especially since the audience is aware that the real murderer is now involved.

As previously mentioned, the de rigueur comic relief wears on the viewer after a comparatively short period, particularly as the actor in question, Lee Tracy as a stereotypical big-city reporter, is also the romantic lead. While a more competent actor might have pulled the combination off, Tracy fails abysmally in both facets of his role.

Yes, the performances are generally weak and the material is dated, but the overall effect of the film holds up well nonetheless, thanks in large part to the strong showing by Atwill. One of the more underappreciated Icons of Horror, Atwill’s career as a star may have been short-lived, but his impact on generations of horror fans hasn’t been, and in recent years he’s been getting some of the recognition that’s due him. DOCTOR X may not be his best work—that must undoubtedly be his performance as Inspector Krogh in SON OF FRANKENSTEIN… but it’s not far from it.

THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME—(1932)

THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME—(1932)

As Merian Cooper and Ernest Shoedsack were putting Robert Armstrong and Fay Wray through their paces by day for KING KONG, Shoedsack and co-director Irving Pichel were working them just as hard at night to produce THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME. With a script based upon a prize-winning story by Richard Connell, Shoedsack and Pichel constructed a first-rate thriller/adventure yarn, one that has been remade at least three times, and spoofed countless others.

The story centers on Count Zaroff, played by Leslie Banks, a wealthy recluse whose one passion is hunting. He lives alone on a private island, save for his servants and his pack of hounds… massive, savage brutes, bred to the hunt. Into this isolated locale comes the lone survivor of a shipwreck: Rainsford, (Joel McCrea) a fellow hunter and adventurer. He finds two castaways from a previous shipwreck, Martin Trowbridge, (Robert Armstrong) a dissolute playboy, given to drinking large quantities of the Count’s liquor; and Eve, Martin’s sister, played by Wray.

Though Zaroff seems the perfect host at first, his sinister persona soon manifests itself, and his true intention for his “guests” is revealed. Zaroff, jaded with hunting even the most ferocious of beasts, indulges his desire for the ultimate challenge, the ultimate hunt—man.

He attempts to draw his fellow adventurer into sharing his hunts, but when Rainsford refuses, he becomes the quarry in a vicious fight for survival: Elude the Count, and live until dawn—and win his freedom and that of Eve. Fail and the Count will celebrate his triumph… with the unfortunate girl as his trophy.

Wray actually has a rather small part in this film, as the conflict between Rainsford and Zaroff is the engine that drives the plot. The desire of both men for Eve is secondary to their true motivation—to kill the other. Both are archetypal Alpha males, and the viewer soon realizes that, even absent Zaroff’s psychotic tendencies, conflict between the two would’ve been inevitable. McCrea does a credible job as Rainsford, but Banks is simply the wrong choice as the uber-hunter Zaroff; in fact, the part would have been perfect for Robert Armstrong. Banks is too soft, too cultured… too effete. The supporting cast, including Armstrong, is superfluous; on-screen for far too brief a time to exert much influence over the flow of the film. The focus is kept on the three main characters, and they drive it along nicely without them.

While not really a Horror Film, THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME certainly contains enough horrific elements to qualify it for this discussion, as does the film’s inherent quality. What’s more, its impact on popular culture far outstrips its notoriety, as many people have seen spoofs of it without realizing what film was being riffed. From Gilligan’s Island to Star Trek, this film has provided inspiration and material to television writers for decades—it’s time more people became familiar with the source of that inspiration.

THE VAMPIRE BAT—(1933)

This, the least well known of the four films in this retrospective, once again paired Atwill and Wray, he as the demented scientist, and she as his unwitting assistant.

The movie also features Melvyn Douglas as a police detective investigating a series of reputed “vampire” murders in a small central European village, and Dwight Frye as Herman, the ‘village idiot’ suspected of the killings.

The film opens as the town burghers are gathered in a closed session to discuss a rash of deaths that has recently plagued the German village of Kleinschloss, deaths that have coincided with a sudden infestation of large bats. Also present is Karl Brettschneider (Douglas), the town’s chief law enforcement officer. The odd manner of the deaths is the topic of the discussion—all the victims were found drained of blood, with two puncture wounds in their jugular veins. The superstitious townsfolk are all too eager to seize on vampires as the cause of the deaths, citing records of similar deaths in the 17th Century. Karl’s not convinced, believing there must be a human agent behind these murders. He insists on conducting a proper investigation, not presiding over a modern witch-hunt.

He leaves them to their superstitions, heading to the home of Dr. Otto von Niemann (Atwill), the physician of Kleinschloss. Karl is involved with the Doctor’s assistant, Ruth Bertin (Wray), a lovely, bright young woman, who resides at the Doctor’s manor house with her hypochondriac aunt, Gussie Schnappmann (Maude Eburn, as the comic relief) and von Niemann’s servants, Emil and Georgiana. The Doctor has examined each of the victims, and can find no clue as to the identity of the culprit. At that moment he is at the home of a survivor of a bat attack, Martha Mueller. As he tries to calm her nerves, her friend Herman (Frye) tries to reassure the Doctor that the bats are harmless; he’s befriended them, and they wouldn’t hurt anyone.

The townsfolk are far less sanguine about the bats, and frankly speaking, about Herman. Kringen (George E. Stone), the night watchman for the town, reports that Herman wanders the streets at all hours, playing with and talking to the hordes of bats that infest the town. He raises the suspicion that Herman is the vampire, feasting on the blood of his fellows, though the Doctor advises him to watch that kind of talk, else he start a panic. That admonition is soon forgotten, however, as the nervous townspeople watch Herman take a bat from a lamppost and tuck it gently into his coat pocket.

Dr. von Niemann returns home, where he finds the detective waiting to discuss the case with him.

The Doctor begs off, stating that he has important work to do, and dismisses the young people to less serious pursuits.

In the town square, the clock tolls midnight.

The window in Frau Mueller’s sick room opens slowly; the woman opens her eyes and screams.

The scene cuts to her lifeless corpse, lying in the morgue as the coroner enters the record of her death.

The cause—the bite of a vampire.

As the burghers gather over Martha’s body to discuss the latest murder, Herman quietly slips into the morgue, and seeing his friend’s body, runs out screaming. To both Karl and the Doctor, this is plainly evidence that the man lacks the capacity to be the fiend for which they are searching. The villagers however see it differently. Kringen convinces them that Herman is the vampire, and that he himself is likely to be the next victim, as he’s trying to warn people about Herman.

The next morning, Ruth is eating breakfast in the garden, as Herman, concealed behind the wall, watches her. Karl surprises her; he’s there to discuss the murders with von Niemann, but seizes the chance to get some time alone with Ruth. The opportunity is soon lost however, as Aunt Gussie appears, in the throes of a hypochondriacal crisis. She has discovered that she is experiencing, “… palpitations of the auricular, ventricular, mitral and tricuspid valves,”—in other words, her heart is beating. The couple reassures her that she will be fine, then go to find the Doctor.

As they leave, Herman sneaks into the garden, distracting the woman so that he might take some of the food. She catches him, however, startling him so that he accidentally cuts his finger. Concerned of course about the possibility of a tetanus infection, Gussie rushes to fetch dressings for the man’s wound.

Inside, von Niemann has been searching his library for information on the lore of vampirism. He’s reading from an old French text on the subject as Gussie enters. She ridicules the legends they are discussing while waiting for Emil to bring the first-aid supplies. As she waits, men from the village enter with news. Kringen is dead, just as he feared—and Herman is nowhere to be found. Not even Karl can deny the appearance of guilt this creates, and gives orders that Herman be apprehended—without harm. The townspeople want to deal with him as one must with a vampire, but Karl forbids it. Herman will be tried in a court of law, and the law will decide his fate. But is Herman guilty of the crimes? Is he in fact a Vampire, an undead creature of the night? Or is there another answer for the mystery that’s plaguing the peaceful village?

Produced quickly by Majestic Pictures in order to capitalize on the forthcoming MYSTERY OF THE WAX MUSEUM, THE VAMPIRE BAT was filmed at Universal, on sets left over from both FRANKENSTEIN and THE OLD DARK HOUSE. This was common practice for the “Poverty Row” producers, those low-budget studios that frequently lacked the assets of the major companies. Often, the smaller of these were without even the rudimentary facilities for motion-picture production. Renting soundstages, sets, even costumes at a major studio was far more cost-effective in the short term. One thing that Majestic didn’t scrimp on was the cast.

Led by Lionel Atwill, one of the most underrated stars of the Golden Age of Horror, this was a group that one would’ve expected to see in one of the great Universal Horrors. With co-stars such as Melvyn Douglas (who had just previously starred in James Whale’s THE OLD DARK HOUSE alongside Boris Karloff and Gloria Stewart), Dwight Frye (veteran of most of the Universal Horrors of the 1930s), and Wray, and filming on Russell Gausman’s spectacular sets, this movie looked far better than it had any right to look.

Directed by Frank R. Strayer, from a script by Edward T. Lowe, Jr., the story may be underwhelming at times; however, the high-quality cast performs superbly with little help from either screenwriter or director. Strayer, forty-one years old when he directed THE VAMPIRE BAT, had been a director for only seven years and had thirty features to his credit prior to this film—not unusual for those filmmakers who earned their living on Poverty Row. Best remembered for directing twelve entries in the popular “Blondie” series of movies (based on the venerable comic strip), Strayer had a twenty-five year long, very productive career. Workmanlike and competent, if not gifted with an abundance of artistic talent, Strayer, and hundreds like him, were the unknown heroes of Hollywood. They might not have gotten critical acclaim and name recognition, but they earned a living doing what they loved while entertaining millions.

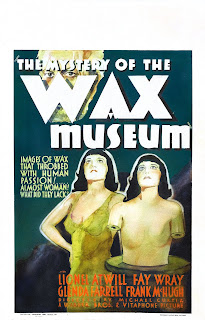

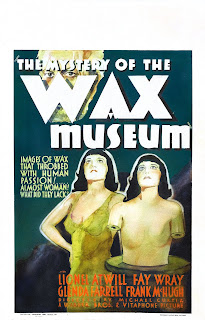

THE MYSTERY OF THE WAX MUSEUM—(1933)

THE MYSTERY OF THE WAX MUSEUM—(1933)

The best of Wray’s Pre-KONG horrors, this was another of Warner’s experimental forays into color films, one that produced much better results than DOCTOR X did the previous year. Not only was the color photography much improved, but the script, the acting, the direction—all was superior to the earlier film.

For the second time Wray is cast opposite Atwill, though her role is actually a minor one. Atwill plays Ivan Igor, the curator of a wax museum, crippled years before in a fire his business partner started to collect on the insurance. As the story shifts from London in the early ‘20’s to New York City’s New Year’s 1933 celebration, morgue attendants are loading a young woman’s body into a waiting hearse. The body is that of Joan Gale, a woman believed to have committed suicide. Florence Dempsey (Glenda Farrell), a newspaper reporter for the Express, is allowed to be present for the autopsy of the woman. Earlier however, a vague figure, wearing a black cloak and hat, stole the body of Joan Gale, lowering it out the window to a waiting truck. When the morgue attendants are sent to bring in the body of the suicide, they find it’s gone, and havoc ensues.

Police believe the body’s disappearance from the morgue is an effort to conceal evidence of murder, despite the earlier finding of suicide, and suspicion turns to a man named Winton (Gavin Gordon), the son of a wealthy industrialist and former lover of the dead woman. Florence however, after interviewing Winton in jail, believes otherwise. The next morning, she accompanies her roommate to her fiancé’s place of business. Her roommate, Charlotte Duncan, (Wray) is engaged to Igor’s assistant, Ralph (a forgettable Allen Vincent). Igor, now confined to a wheelchair, has other hangers-on about the place, ne’er-do-wells such as Darcy (Arthur Edmund Carewe), a seedy looking, self-styled “Professor” and drug addict, and a deaf-mute named Hugo (Matthew Betz).

Florence

Florence discovers a wax effigy of St. Joan of Arc that bears a striking resemblance to the missing dead woman, and becomes suspicious of the museum.

At the paper’s offices, she examines photos of the Gale woman.

She is convinced that the figure of Joan of Arc is the image of the dead woman, and that the body’s disappearance, perhaps even the woman’s death, is connected to Igor's waxworks.

Florence’s investigation of the waxworks leads her to follow Darcy to Winton’s liquor supplier, a bootlegger named Worth (Edwin Maxwell), who is the man who started the fire that injured Igor twelve years before. She breaks into the warehouse where Worth stores his illegal liquor, discovering a hideous creature, face twisted and deformed. It is the same monster who stole the body of Gale from the morgue. When Darcy is arrested leaving the place, all the police can find are bootleg bottles of whiskey. However, while searching the man, by now beginning to suffer through withdrawals, a watch belonging to a Judge Ramsey, who disappeared months earlier, is found. Detectives begin a rigorous interrogation of the junkie, who finally cracks under the strain. Yes, he killed Judge Ramsey—who died because he resembled Voltaire. That’s the secret of Igor’s amazingly life-like effigies. They look so realistic because there’s a dead body concealed in each one. Joan of Arc wasn’t merely modeled after a dead woman; the woman herself is sealed within the waxen shell. In addition to supplying victims to Igor, he was tasked to keeping a close tab on Worth while working with him, to aid Igor in exacting his ultimate vengeance against the man who crippled him.

During the interrogation of Darcy, Florence, accompanied by Winton, goes back to the wax museum to search for clues. Prior to their arrival, however, Charlotte shows up, looking for Ralph. Igor, obsessed by her resemblance to his lost ‘masterpiece’, his sculpture of Marie Antoinette, tricks her into his basement ‘workshop’, then stands up to reveal that he’s not as infirm as he wants people to believe. He grabs Charlotte, telling her she will have eternal beauty as his Marie Antoinette. She struggles against him, striking his face. In the film’s most iconic scene, it shatters, breaking apart like the wax mask it was, revealing the twisted face of the creature from the warehouse. Charlotte screams, then passes out.

Florence, Ralph, and Winton, now together in the museum, hear the screams and head downstairs. After breaking into the concealed workshop, Ralph fights Igor, but is knocked unconscious. Florence and Winton look on in horror, unsure of how to help Charlotte, herself unconscious and strapped to an operating table, as a vat of boiling wax begins filling a sprinkling system suspended over her. As they stare at the scene unfolding below them, the police, in response to Darcy’s confession, burst in. They are forced to shoot Igor, who falls into the massive vat of wax. Ralph comes to, pulling Charlotte out of harm’s way just as the molten wax starts to rain down.

Florence has her story, and apparently, her man. Winton has fallen madly in love with her, proposing to her in the midst of their adventure. She starts to tell her editor, when he also asks her to marry him. With a quick glance out the window at Winton cooling his heels in his expensive car, she tells her editor yes, and the film ends on a happy note.

Warner Bros. in the 1930s was known for it’s gritty, realistic crime dramas, not Horror films. However, even by those standards this is an atypical picture. It is definitely a pre-code film, meaning it was produced before the strict guidelines of the Motion Picture Production Code came into use in 1934. Had this movie been produced as little as one year later, it would have been a far different film. Not only would the mention of Winton and Gale having lived together have been banned, but also would the device of Darcy being a junkie, and the background that Joan Gale had been a narcotics user. A humorous scene between Florence and a cop at the station, in which she snatches a racy magazine out of his hands, while inquiring about his, “… sex life,” would certainly be out, as would other questionable remarks by Farrell’s character. One need only compare this film to it’s 1953 remake, the Andre de Toth-directed HOUSE OF WAX, to get a sense of what a post-code version would have resembled. It is fortunate for fans of this film that it was produced in 1933, not 1934, as the 1933 film is far superior to the remake, in large part due to the increased realism and maturity of the material.

Though Wray’s role in this production is minor, it is the one that stands out as the most memorable. She, after all, is the object of the villain’s obsession, and the image of the beauty that he longs to recreate. And to her is given the honor of unmasking the evil within Igor, both figuratively and literally, in the film’s spectacular dénouement.

Long thought to be a ‘lost’ film, a complete print was fortunately found in the private archive of Jack Warner, and restored to its full glory in the 1980s. MYSTERY OF THE WAX MUSEUM remains a glittering diadem from Horror’s Golden Age.

Every era of Horror has had its female icons—more popularly known as “Scream Queens,” whether they were virginal victims or vengeful vixens. In the ‘40s it was Evelyn Ankers and Simone Simon; in the ‘80s, Sigourney Weaver and Jamie Lee Curtis. But through all the decades, one name, and one beauty, has reigned over them all—so much so that now, nearly eighty years since her famous scream first thrilled moviegoers she is still a household name. The role of Ann Darrow may have been the sparkling diamond in Fay Wray’s career—but it was far from the only jewel in the crown of Horror’s first Queen.